|

NanoWriting - the big challenge of writing about small things If you want to see many a scientist squirm, ask them to write a story. Writing about their work is easy, as long as it's for a journal to be shared amongst fellow researchers in their field. There's just something about the prospect of writing for a non-scientist reader that flicks a trigger in the head of most scientists and brings down the curtain on their willingness to share. Part of this is through worry, and part is through fear. Both are unnecessary, yet both have emerged at a number of science writing workshops held recently by SAASTA.

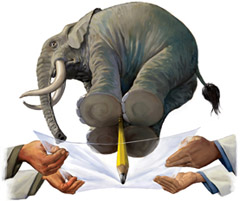

As a journalist I have interviewed enough scientists to know that most burn with an unbridled energy for their work. Unlocking that energy is easy: ask the right questions; show a genuine interest in their work; and the archetypal reticent scientist soon morphs completely into a different animal that just won't shut up! However, that's as long as they're not the one who'll end up writing the story. There's something about them putting the proverbial pen to paper that makes their eyes twitch, their lips quiver, and their brain waste away. Their worry is that sharing their work with non-scientists somehow injures their academic credibility. Don't laugh, it may sound incredulous but this is a commonly expressed belief amongst the scientists whom we train to write for the popular media, and which they sense exists within academia – publish or perish, but keep it to academic journals. Outside of such a sentiment making academia sound like some form of 'old boys' club' with secret handshakes and codes of conduct, it risks creating the impression that science is inaccessible and irrelevant to all but a select few; which of course it isn't. We are all constant consumers of science, and most scientists we speak to believe this passionately. Sprinting into the unknown However, the fear that many scientists seem to have about writing is also linked to this publishing in academic journals. The integrity of science relies on peer review, and this depends on the accuracy of research and adhering to guidelines in presenting it in journals. This involves stripping away sentiment, sticking to the facts, and being as detailed as possible. So when writing about research invites creatively embellishing the science to describe and explain it, and replacing detail with colour, some scientists hit something of a brick wall. It's as if they're sprinting into the unknown. Of course they forget what it's like at a braai. The reality is that writing a story is the same as telling one, and we all tell stories around a braai. The difference with writing a story is that it gives us time to think about it more – to make the story more colourful, more exciting, and more interesting. In a word: better. It also makes it a little easier and a lot more fun, because we can dive into the creative use of analogies, which provide context for non-scientists. However, analogies are thin on the ground when writing about something that most people cannot see, such as nanoscience and nanotechnology - the study and application of matter on an atomic and molecular scale. The big challenges of the very small To put things into context, one nanometre (1nm) is one billionth of a metre, or one millionth of a millimetre. That's approximately the width of four gold atoms placed next to each other, which is hard to imagine. To further complicate things, particles smaller than 50nm stop following the laws of classical physics and start following the laws of quantum mechanics; and to quote the Nobel Prize winning physicist Richard Feynman, "If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don't understand quantum mechanics"! So does this make analogies in nanotechnology impossible? No, just slightly more challenging. They also come with a word of caution: some analogies used to explain nanotechnology have backfired, especially when considering proposed regulations around this emerging focus of science. Professor Patrick McCray, of the Centre for Nanotechnology in Society at the University of California, Santa Barbara, covers some of these on his Leaping Robot blog. Here are some good examples, though, as inspiration:

By Daryl Ilbury, Media Coordinator, SAASTA |