|

Grab attention with your press release

Dr Oliver Dreissigacker

Former astronomer and magazine editor, freelance science writer,

Mannheim, Germany

Unless your paper appears in Nature or Science, you can't rely on an editor scanning the journal or the preprint archives, stopping by your work and getting a hold on the story.

You need to pitch it! Here is how you do it …

Before you sit down and sketch the press release - maybe together with a press officer, should your institution have one - you should come up with a punch line that describes the essence of the progress that your work yields. Don't be afraid to repeat this punch line - in different words - in the various parts of the release. It should also be your primary headline.

Throughout the release, avoid superlatives if not absolutely necessary, that's for advertising text. Superlatives make editors suspicious; they might turn down a story just under that first impression.

Don't exaggerate your own achievement, and give credit to earlier work on the subject(1).

The subheading (byline, secondary headline) should contain information on the team and on the means, with which the results were achieved - theoretical work, experimental, observational, computational or similar.

The abstract - no more than, say, 500 characters - ought to be a description of the problem that your work addresses, what the result is, and how it was achieved (with which instrument, super computer, etc). This paragraph should be in type-set in bold. It's the last chance to convince the editor to keep on reading further if he or she isn't yet hooked.

Most important things first!

Usually, the press release has a top-down approach. That means, the most important information is on top and the editor can just cut the text when he's at his text limit. If he decides to make a more extensive feature article, he is going to tell a story completely anew from his own perspective anyway. So, better stick to top-down, the same order in which a typical short news report is written.

Within the main text - which should not be longer than seven paragraphs or so - introduce the key persons that were involved in the research. Make sure you offer personal quotes from any of them. Ideally, two quotes a person (maximum five or six quotes in total, when there is only a team of two). Those quotes should give the basic explanations of what was done, how it was done, what the result is and what its importance is. The reason for such a procedure is not only to make the story more lively, but you offer the editor more points to which he can connect. These anchor points can be:

- Object relevance - the topic of your research. The general public is especially interested in Black Holes, Exoplanets, Space Weather, or other potential threats like GRBs, Supernovae, NEOs or alike. It could also be that the editor is an expert in your field.

- Subject relevance - one or more team members might have been interviewed by the editor before, or he/she is even a personal acquaintance.

- Geographical relevance - one or more team members might have a connection to the area where the editor's piece will be received. Or the instrumentation has a contribution from the editor's region.

An elegant opportunity to repeat the punch line - aside from the headline and a personal quote - is a so-called "pull quote": a field with a border or a light background colour, and one key sentence in a slightly larger font size.

Then: the imagery. A picture tells more than a thousand words! This is also - and especially true - with press releases. They should be eye-catchers! If possible, try to cover all three connections (a-c) above. Don't be afraid to offer a hand-sketched illustration if necessary. Even if online media don't have time and/or resources to give it to an illustrator, monthly magazines may do so! The least you achieve is to give the editor an idea of the geometry of the problem or the setup of your experiment.

Don't be too humble, offer photographs of your team and yourself - at the telescope, in the lab, with the computer cluster, doing maths or sketches on a black board, or running simulations on a computer. Readers are usually interested, who is doing the research, and how. Show them!

Finally: provide background information. The most important thing is the complete citation of the paper, optionally details of the institution and the instrument(s) involved, followed by contact information. The perfect press release would name all (major) authors (point b), including a mini-bio (point c), nationality, link(s) to his or her web site(s), a remark in which languages the authors may respond or give interviews and the office hours. The latter is only an advantage, of course, when everyone is available at these times once the release is issued.

Keep in mind that daily media need your response within an hour or two, so make sure you stand ready to react!

More time - more quality: The only way to broaden this time window is using an embargo. For example, "Nature" and "Science" make all content available to reporters four days prior to publication. That makes the news appear more important on the one hand and gives the journalists enough time to plan ahead and contact the scientists on the other hand. You need to be aware that online media usually have limited resources and must lay out a week's schedule on Monday mornings, at least for the feature articles!

So, now you have a press release, but who send it to?

Your press officer will certainly be familiar with the local and national press. But, what about international titles or freelance science writers abroad?

The easiest way to reach them is through the American Astronomical Society's e-mail service or similar services that may exist in other countries. Check their web sites for the e-mail address of the press officers and ask for directions. Once you have submitted the text-only press release, they will re-distribute it shortly after, either to reporters only when your release is under embargo, or to all other subscribers if not.

Make sure your release also shows up on your institution's web site to allow access to the imagery.

Of course, when it is embargoed, protect text and imagery with a password that must be included in the version that's going out to reporters, as well as the full release's URL.

In the case of Nature and Science and maybe other journals, you can submit your release in advance and it gets included in the press package. This again raises the chances of getting the editor's attention, since he knows he has more material to work with.

One side note: These journals require that the journalist must ask the authors for image use permissions! So please have all imagery at hand, in case you're asked for high resolution versions or files in Photoshop format that have the text in different layers that allows language adaption.

Sure, life's not perfect and most press releases (or articles) aren't, either. But once you understand what information journalists need to turn your research into a story and when, they will - at least - give your material a close and benevolent look.

(1) During the CAP conference in 2005, representatives from institutions that are affiliated with NASA were sharply criticised for what Europeans called unfair practice. Yet again, the recent reporting on the Kepler satellite seeing phases of an exoplanet suppressed to mention an earlier detection of the same phenomenon with the small French-led CoRoT satellite (Snellen, I.A.G., de Mooij, E.J.W., Albrecht, S.: "The changing phases of extrasolar planet CoRoT-1b". In: Nature 459, 543-545, 2009).

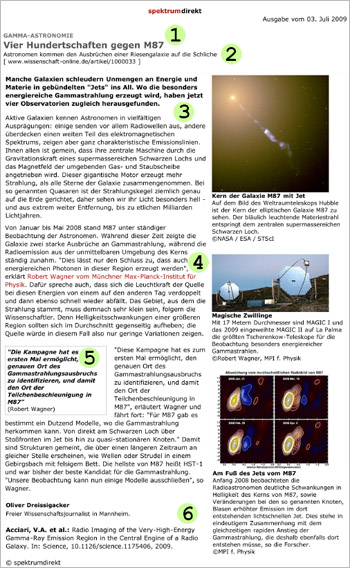

Example of a published article with elements corresponding to those of a press release: Headline (1), Subheading or Byline (2), lead text (3), Hyperlink to scientist's web site (4), pull quote (5), citation (6). Please note the different kind of images used, including descriptive captions and copyright remarks. © spektrumdirekt / dre. View large version |

|

A collage of photographs that appeared in the past months in reports on astronomy, physics, ocean and climate research. This way, the scientists give an insight in their working environment and raise interest in their research. © misc. / dre.

View large version |

|